1906 Earthquake

At 5:12 A.M. on April 18, the Wednesday after Easter Sunday, 1906, an estimated 8.3 magnitude earthquake shakes San Francisco for 48 seconds. Tom Cole writes, “The greatest damage occurred in North Beach and the financial district, where swampy marshes and the old Yerba Buena Cove had been filled during the Gold Rush. The land there acted like jelly, trembling hideously, and magnifying the effects of the earthquake. But the earthquake itself accounted for only about 20 percent of the ruin San Francisco was about to suffer.” Nearly half the residents became homeless after the resulting firestorm destroyed four-fifths of the City.

Gallery

Architect George Kelham is hired to build a new Palace Hotel after the original is destroyed by the earthquake and fire. Kelham will stay on and win the competition to build the new city’s Main Library on the former site of the City Hall after it is rebuilt on Polk Street. (Author’s Collection.)

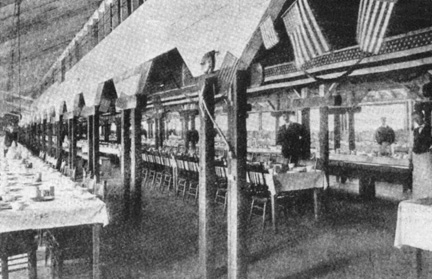

Thomas Williams, new owner of the Ingleside Race Track in 1905, offered his facilities free of the charge for the city to provide more permanent housing to the earthquake refugees living in tent cities. Windows were installed in the horse barns, which were also cleaned and painted. The dining hall and ladies bedchamber are shown below. The Ingleside Model Camp opened for 484 men and women in October 1906. The track itself never reopened. (Courtesy Margie Whitnah.)

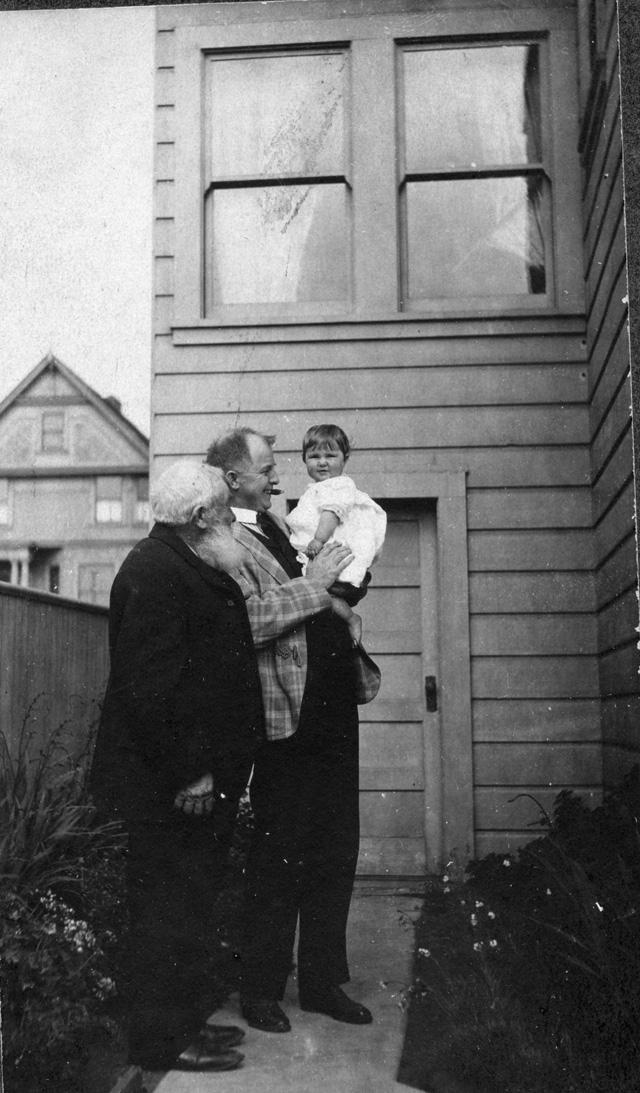

The day after the 1906 earthquake, the Weir and Shank family were happy to be together and safe so they took pictures outside their undamaged home at 61 5th Avenue near Lake Street, to show they were okay. Born in Sydney, Australia, in 1835, Scotch Presbyterian, James Weir had come to San Francisco in 1852 on the same boat from Honduras as Leland Stanford and Augustus Howell. He made a living in the construction business while he searched for silver in his Nevada mine near Winnemucka. For six weeks, no indoor fires were allowed anywhere in the city for fear of new fires caused by faulty gas lines and broken chimneys. Charlotte Weir, here with her brother-in-law, John Shank, cooked meals for her family and some of the seventy thousand refugees camping at the nearby Presidio after following orders to move their stove outside to prevent fire.(Courtesy Elizabeth Mettling.)

Tom Cole writes that “San Francisco enjoyed a brief return to Gold Rush democracy as all classes and races mixed and chatted at the sidewalk kitchens. Edward Hart remembered the adventure of it all and recalled the melancholy when ‘the stoves could be brought back into the house from the sidewalk…when that day came…that was THE day…the streets looked empty.’” Young Sally, being held by her dad, next to her Grandfather James Weir, would be glad to find her baptism record safe at her family’s church years later after her birth certificate was destroyed in the earthquake. (Courtesy Elizabeth Mettling.)

Leland Stanford’s mansion on Nob Hill before it was destroyed in the fire that followed the earthquake. (Author’s Collection.)

Sally and her husband would buy a new home on land once owned by Leland Stanford in Miraloma Park after her mother said, “Buy this house – it has a dining room in it.” Nearly 40 years later, Sally took this picture of her mother Elizabeth, Aunt Charlotte, husband Gunnar, niece Elizabeth Mettling, and sister, Charlotte, in that dining room in 1945. (Courtesy Elizabeth Mettling.)